How democracy vouchers could change local politics in LA and beyond

“We've seen them diversify the pool of donors. “We've seen them expand who can run for office. And we've seen them boost political engagement. So that's why we're working so hard to pass this.”

April 14, 2024

Welcome to the sixth issue of Report Forward by journalist Alissa Walker.

THE BIG REPORT

Democracy vouchers are like a ticket to voter engagement. Photo by Tom Latkowski

Are you a Los Angeles city resident who donated to a candidate in the March primary? Maybe, by poking around online, you found out about the city’s program which matched your donation 6:1 (but only if your candidate had already raised enough money to access the program itself). You may be surprised to learn that, of the $7.65 million total donated in the city’s March primary, just $1.7 million came from people who live in LA City like you, with those matching funds kicking in another $1.9 million. The biggest chunk of donations came from people outside of LA City: $2.9 million, or 38.4 percent. And another $1 million was donated by non-individuals such as corporations, unions, partisan nonprofits, and political action committees (PACs) inside and outside of the city. Yes, despite the city matching so many LA resident donations, about half of the money in LA’s 2024 primary election (47.5 percent) still came from groups and people who aren’t even in LA. Is this really how it’s supposed to work?

Now imagine it’s the 2028 primary. You receive four coupons with your ballot, each valued at $25 each, which can be allocated to the fundraising campaigns of the candidates of your choice. Contributing to an LA candidate is as easy as voting using a mail-in ballot — you can also do it online — but instead of money coming out of your pocket, these donations would be paid for by the city itself. These are called democracy vouchers, and even though the whole thing sounds too good to be true, this system is currently in place in Seattle, coming soon to Oakland, and, thanks to a dedicated coalition of campaign finance reform groups, closer to reality in LA than you might think. “We've seen them diversify the pool of donors,” says Tom Latkowski, a co-leader of Los Angeles for Democracy Vouchers and the author of Democracy Vouchers: How Bringing Money into Politics Can Drive Money Out of Politics. “We've seen them expand who can run for office. And we've seen them boost political engagement. So that's why we're working so hard to pass this.”

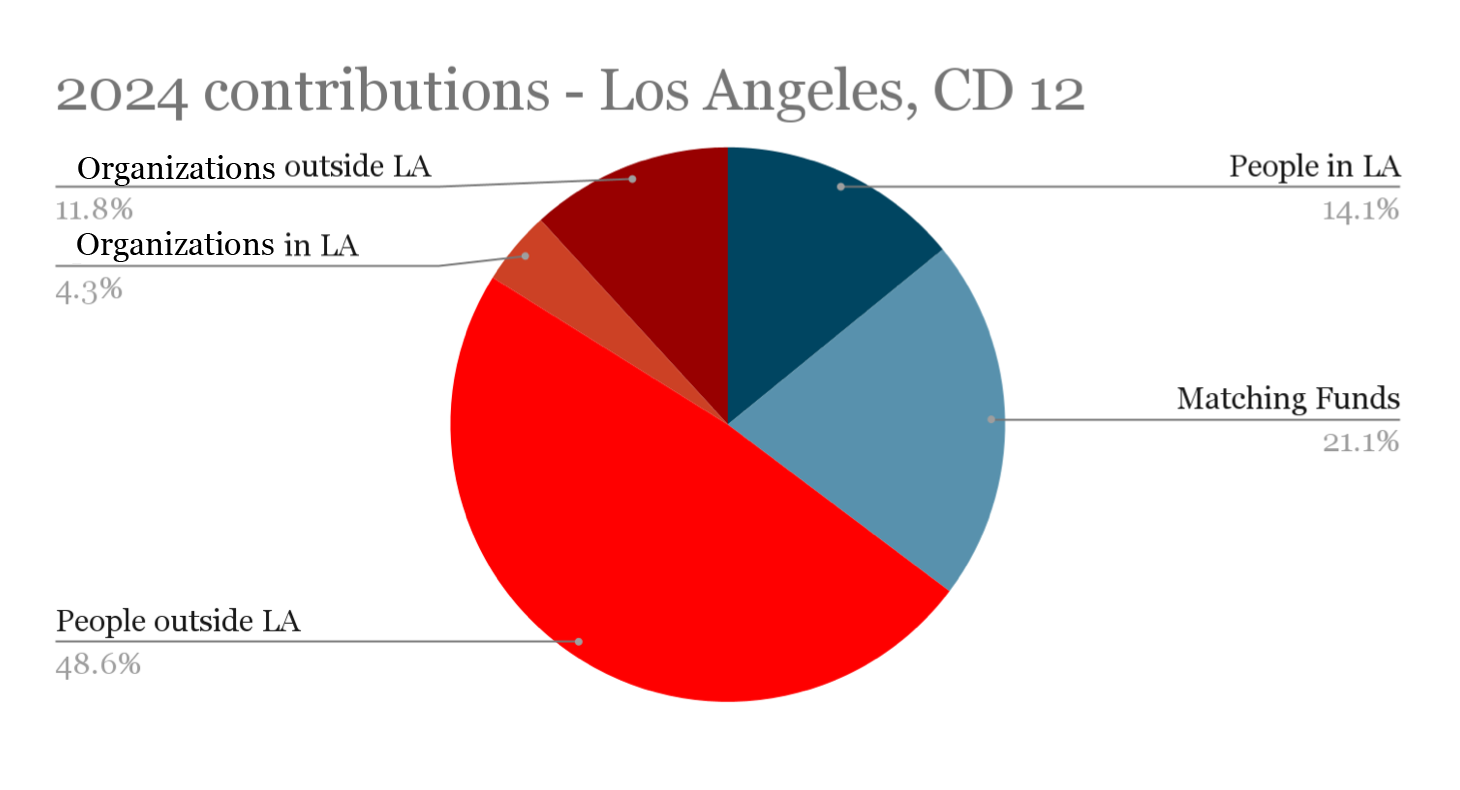

A majority of LA’s 2024 political contributions came from people outside LA and non-individuals, including organizations such as corporations, business associations, unions, 501(c)(4) nonprofits, and political action committees (PACs)

In the Council District 12 race, where former Republican John Lee won in the election in the primary with 62 percent of the vote, 60.4 percent of all contributions came from outside of LA. Created by Tom Latkowski of Los Angeles for Democracy Vouchers, with additional edits by LA Forward Institute.

Last June, LA’s City Council adopted a motion introduced by Councilmembers Nithya Raman, Hugo Soto-Martinez, and Marqueece Harris-Dawson that will soon deliver recommendations for how the city could implement its own democracy voucher program like Seattle. And last September, Latkowski and his Los Angeles for Democracy Vouchers co-leader Mike Draskovic published the most comprehensive local report on the topic yet: “Exploring Reform: A Compendium of Research, Reports, and Modeling of Democracy Vouchers in Los Angeles.” Crunching two decades of campaign finance data, the need for reform is clear: Angelenos who donate to city campaigns tend to overwhelmingly come from the richest and whitest neighborhoods. That means many candidates spend time and energy courting those likely donors instead of engaging more with their own potential constituents, says Draskovic, who is also co-founder of the Democracy Policy Network. “They're listening to people from wealthier backgrounds and their priorities, and they're not getting a holistic sense of what Angelenos want to see in their public officials.”

A decade ago, Seattle was in the same situation. Before the city’s implementation of democracy vouchers, one of the best predictors of whether or not someone was going to be a donor was whether or not their house had a view of the water. Since democracy vouchers were first rolled out in 2017, astonishing data shows a remarkable shift in campaign contributions, with the demographics of donors aligning more closely with the demographics of voters across age, race, and income. These figures also have become more representative with every subsequent election. Additionally, the amount of campaign money from outside the city has dropped by 36 percent. And because public financing lowered the bar for entry, the average number of people running in Seattle City Council races has increased after democracy vouchers were implemented.

Democracy vouchers might also be more effective than other efforts to increase participation in elections, like universal mail-in voting or synching up local races with federal races. Vouchers are sent out regardless of voter registration status — in Seattle, vouchers go to all citizens and permanent residents over 18— and there is strong evidence that they really do move the needle on turnout, says Latkowski. “In Seattle, we've seen data that when previous non-voters use a democracy voucher, they then become six to 10 times more likely to vote.”

In Seattle, the number of individuals participating in the campaign finance system has grown over 500 percent since democracy vouchers were introduced in 2017. Chart by Seattle Ethics and Elections Commission

To their credit, LA’s elected officials have already taken a few key steps to try to level the campaign-finance playing field, including the 2019 amendment of the existing matching funds program to “supermatch” donations 6:1. (Although only thanks to pressure from reform advocates and the need to save face amid a string of scandals.) In this year’s elections, the maximum eligible donation of $129 for a city council race, when matched, can become $903 — notable because that will make the contribution of an LA city donor equal to the $900 maximum donation allowed by any individual or entity inside or outside the city. Those 2019 amendments also reduced other thresholds for candidates, including the amount of donations they must raise in order to qualify for matching funds. Those thresholds were not lowered enough for many advocates’ taste, who argue it’s still too hard for candidates — including some who did not qualify in March’s primary — to unlock the benefits.

But while matching funds are better than nothing, anything that requires disposable income to participate still creates a barrier, Latkowski says. “If I'm someone with $0 of disposable income, and my donation gets multiplied by six, well… six times $0 is still $0. And so there's just a lot of people that are left out.”

It’s easy to see why voters might get more energized about a candidate when they have what feels like Monopoly money to donate. But because they incentivize direct interaction with voters, democracy vouchers can also dramatically change the way candidates campaign. Vouchers can only be redeemed from potential LA city constituents — candidates can physically collect them when they canvas a neighborhood or table at community events — which rewards in-person engagement and shifts attention away from wealthy outside donors. This has also been the way LA’s progressive campaigns have been winning elections lately. In this year’s March primary, a focus on door-knocking for Ysabel Jurado (Council District 14) and Jillian Burgos (Council District 2) landed the two grassroots candidates in their respective runoffs. Jurado and Burgos poured donations back into canvassing — and funding even more time spent interfacing with voters.

While democracy vouchers don’t eliminate the power of wealthy donors — or wealthy candidates like Rick Caruso, who spent $100 million of his own money to lose the 2022 mayoral race —Latkowski and Draskovic argue more public financing can start to chip away at their influence.As cities and states move towards more robust publicly financed models, they can place additional conditions on candidates who accept that funding. LA’s democracy voucher program could be custom-designed to build upon its matching funds system or implement a full public financing model, where candidates get a lump-sum grant to pay for their entire campaign with public money. (In Arizona and Maine, these voluntary “clean election” programs are so popular that state candidates often opt to not accept private money at all.) Modeling by Latkowski and Draskovic as well as the California Clean Money Campaign shows this hybrid model could be implemented citywide in LA for an estimated $12 to $20 million per year — a corruption mitigation tool that’s just 0.15 percent of the city’s budget.

In the 2022 election, the average donation from LA’s majority white ZIP codes was 2.28 times the average donation from majority people of color ZIP codes. Map from Exploring Reform: A Compendium of Research, Reports, and Modeling of Democracy Vouchers in Los Angeles

Ideally, LA’s City Council would place a democracy voucher proposal on the November 2024 ballot as part of a package of good government reforms, including independent redistricting and council expansion (and, hopefully, much-needed ethics reforms). But it’s also possible that a decision like this could be put forth by a to-be-created charter commission, another option recently advanced by the council’s Ad Hoc Governance Reform committee. Plan C would force advocates to gather enough signatures to put democracy vouchers on the ballot as a citizen-sponsored measure, which would be arduous and expensive for an ethically challenged city like LA that doesn’t have time or money to waste.

Cleaning up the money in LA politics doesn’t end with a voucher system, of course. The holy grail of campaign finance reform is overturning the 2010 Supreme Court ruling Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, which removed spending caps for the secretive independent expenditure committees that currently dump millions of outside dollars into LA’s elections. (This year, $1.35 million in independent expenditures were spent in an attempt to beat Raman, who still won outright in the primary.) But until that happens, democracy vouchers are something that the city of LA could easily implement to make its elections more representative and more fair — and to Latkowski and Draskovic, the evidence from Seattle is irrefutable. “To see that many new voices come into the campaign finance system, that’s meaningful,” says Draskovic. “But to see the diversification of the donor pool and the candidate pool, and just the sheer number of people participating in that voting who otherwise weren't voting before — that’s just remarkable.”

Want to learn more about what democracy vouchers could do for LA? Watch this video briefing held by LA Democracy Vouchers featuring local experts, reform advocates, and elected officials.

PROGRESS REPORT

Just 12 months after Measure ULA began collecting a transfer tax on LA city real estate transactions over $5 million to fund affordable housing efforts, 4,652 LA households have received emergency rental assistance from this fund. That’s an estimated 11,000 Angelenos who have stayed housed since voters approved the initiative in 2022, in addition to nearly 5,000 renters who received legal representation or advice through ULA programs. And, according to “Measuring LA’s Mansion Tax: An Evaluation of Measure ULA’s First Year” published by researchers at Occidental College, USC, and UCLA this month, not only has the $215 million generated by ULA to date become the city’s single-largest source of revenue for affordable housing and homelessness prevention, it’s more than twice the amount that the federal government gave LA for similar programs in the past year.

ULA supporters gather at the 100 percent affordable Santa Monica Vermont Apartments. Photo by United to House LA

As the report notes, ULA’s revenue has also trended upwards despite an overall cooling of the local real estate market attributed to many factors outside of LA’s control, like sky-high interest rates, rising construction costs, and inflation. But ULA’s money is also helping affordable housing developers navigate those same financial challenges. Earlier this month, ULA supporters rallied in the courtyard of the Santa Monica Vermont Apartments, a 187-unit affordable housing complex atop the B line Metro station, which ran into financing issues when its construction interest rate was raised from 2.7 to 7.5 percent, jeopardizing its completion. Now, $2.5 million of ULA funds will go towards the Santa Monica Vermont Apartments — one of nine projects set to be expedited through a new proposal to use ULA money to close affordable housing funding gaps. ULA’s support was critical, according to Tak Suzuki, Director of Community Development at Little Tokyo Service Center. “Without Measure ULA funding we would be unable to get this project finished.”

LOCAL REPORT

14 percent of LA’s rental housing has three bedrooms or more, creating widespread overcrowding in a city of renters where one-third of families have four people or more. (In comparison, 70 percent of LA’s homes owned by residents have three bedrooms or more.) But social housing could help address the shortage.

$30 million would open and staff existing restrooms at Metro rail stations across the region, providing riders unprecedented comfort and safety while saving cleaning and maintenance dollars. It’s just one way that Metro’s $134.5 million plan to create an in-house police force would be better spent, according to ACT-LA’s new campaign.

16 to 26 percent of a family’s income is spent on child care per child in LA, on average, while the precarious financial state of local child care facilities means many child care workers are severely underpaid. Last month, the City of LA’s Community Investment for Families Department report and recommendations were approved for a new citywide strategic approach, the Child Care Equity Initiative.

300 emergency calls have been diverted from LAPD to new unarmed response teams since March 12, Councilmember Monica Rodriguez announced last week. Years in the making, the new Unarmed Model of Crisis Response (UMCR) pilot program finally launched, with two two-person service teams operating in three service areas around the clock.

$4.3 billion in stormwater investments must be made by 2040 to prevent devastating flooding and deadly heat, according to the Los Angeles County Climate Cost Study. Of the total estimated $12.5 billion in climate adaptation costs needed, the Center for Climate Integrity study recommends over one-third be devoted to stormwater interventions like bioswales and permeable pavement.

STATE REPORT

EXTREME MEASURES: A new database by SPUR tracks the 208 land-use ballot measures passed in the state since the1970s and how they’ve impacted housing supply. LA County leads with 25 measures that have restricted housing production.

NOBODY HOME: Nine California agencies have spent billions on 30 homelessness programs, but the state hasn’t tracked the effectiveness of this spending since 2021, says a new California State Auditor report.

EMISSIONS OMISSIONS: California is not on track to meet its climate goals and will need to triple its efforts to hit its 2030 targets, says Next 10’s California Green Innovation Index. The largest increase is in the transportation sector, where emissions went up 7.4 percent.

NOT GOING WELL: Efforts to make oil companies pay to cap and clean up over 2 million orphan wells aren’t working and California might be on the hook for billions in remediation costs, according to a Capital & Main and ProPublica investigation.

FIELD REPORT

California Community Foundation CEO Miguel Santana in conversation with Investing in Place executive director Jessica Meaney. Photo by Investing in Place

Over 90 Angelenos joined Investing in Place for “The Public Way: Making Infrastructure Work for People,” the organization’s winter convening highlighting the need for a citywide capital infrastructure plan, a multi-year strategy to fund and implement public works improvements. Speakers included LA City Councilmember and chair of the Budget and Finance Committee Bob Blumenfield, Destination Crenshaw CEO Jason Foster, and California Community Foundation CEO Miguel Santana, who served as Chief Administrative Officer at the City of LA during the previous budgetary crisis and said not having a capital infrastructure plan in place made his job harder. “A plan helps you define what’s most important,” said Santana. “Before we get to the distribution of resources or prioritization of which communities get what first, we need a shared vision of what kind of community we want to have, from the perspective of the community.”

Coming up next…

Social Justice Partners LA is holding its legendary Fast Pitch event back in-person again at the California Endowment on Tuesday, April 23. LA Forward Institute’s own Godfrey Plata will be one of the nonprofit leaders sharing their visions for LA! Tickets available here.

REPORT IN

Hi, Alissa Walker here — I’ll be compiling Report Forward every month. Please send reports, studies, white papers, and big policy wins to me at reports@laf.institute — and forward this to someone working to make LA a better place.

Want to make sure to get these issues every month? Sign up for our email list below!

Water, water, everywhere

Los Angeles County still only captures a fraction of its stormwater — less than 20 percent. But thanks to a major countywide effort, LA's water might finally be headed in the right direction.

February 13, 2024

Welcome to the fifth issue of Report Forward by journalist Alissa Walker.

THE BIG REPORT

An infiltration pond on the campus of the Carthay School of Environmental Studies Magnet soaks up stormwater — but most of LA’s rain is funneled to the ocean. Photo by Miles Leicher

Another atmospheric river, another week of record-setting rainfall — and another chance to watch in utter disbelief as billions more gallons of water are flushed out to sea. Los Angeles County only captures a fraction of its stormwater — less than 20 percent — despite the fact that voters passed a transformative ballot measure to catch, clean, and consume more stormwater nearly six years ago. Measure W, a parcel tax on impermeable land like parking lots and driveways, now funds the county’s Safe Clean Water Program (SCWP) to the tune of $280 million each year. That money is, in turn, doled out as grants for projects that turn gray impervious surfaces to green permeable ones — effectively depaving LA’s near-ubiquitous hardscape. But despite a dependable flow of cash, progress has been more like a slow drip. In 2023, an update on the program revealed that only 30 acres had been converted into green space.

To see these figures during years when LA has watched historic levels of precipitation fall from the sky has been downright excruciating for Mark Gold, who, as the longtime president of Heal the Bay, had been sounding the alarm on watershed health for decades. But LA’s water might finally be heading in the right direction. Gold, who is now director of water scarcity solutions for NRDC, is one of the co-authors of Vision 2045, released in December of last year by Heal the Bay, NRDC, and LA Waterkeeper as a course-correction for funding SCWP projects that sets sweeping new targets for stormwater management, including a goal to capture nearly 100 billion gallons annually by 2045. “How do you make a document like this so it actually leads to change in the program while improving water supply and water quality and also improving communities?” says Gold. So now the real work begins: translating more of that money into tangible, day-to-day benefits for the county’s most marginalized residents, who are more likely to experience the dangers of impermeable surfaces like flooding, pollution, and extreme heat.

The crucial first step was getting everyone in the county on the same page. The Vision 2045 release was timed to coincide with the passage of the LA County Water Plan, approved by the Board of Supervisors in December with a goal to source 80 percent of LA’s water supply locally by 2045. “As climate change makes our imported water resources less reliable and more expensive, I would like to see the majority of our stormwater be diverted for beneficial reuse rather than washed out to the ocean where it pollutes our coast,” said Board Chair Lindsey Horvath when the plan passed. The extensive outreach process for the plan has aligned all 200 water agencies in the county behind this goal, which is now the same as the SCWP goal, says Gold. “We make it abundantly clear that the 80 percent of local water by 2045 target really guides everything else.”

By 2026, the Alondra Park Multi-Benefit Stormwater Capture Park in Lawndale will treat stormwater onsite and prevent pollutants from entering the nearby Dominguez Channel. Rendering via Los Angeles County Board of Public Works

Unlike the state’s climate funding, which has to be clawed back from cuts made every year during the budget process, the stream of Measure W revenue is reliable year to year. But last February, an LA Waterkeeper report first raised concerns about SCWP implementation, noting that after a strong start, the number and quality of grant proposals had declined. Gold says one of the reasons for this is fairly typical when passing infrastructure-funding mechanisms like Measure W: a slew of “shovel ready” projects planned by big agencies long before the measure went into effect quickly applied for and got the first round of funding. Consequently, many of the projects that have been funded are building or repairing traditional pieces of water infrastructure, some of which actually required more paving, like cisterns and catchment basins.

Water might be captured through these traditional projects, but they’re not necessarily the types of interventions so desperately needed to break up LA’s concrete landscape: nature trails, open space, wildlife habitats, biodiversity corridors, microforests, and most critically, new parks. LA is exceptionally park-deprived, ranking 80th out of 100 cities in an annual report by the Trust for Public Land, with “very high need” neighborhoods that have less than one acre of park per 1,000 residents, according to the county’s 2022 parks needs assessment. Which is why, the report notes, the “pay as you go” approach of the SCWP isn’t working. Vision 2045 calls not only for a financing system that can help plan bigger projects year-to-year, but also for better collaboration with two other countywide infrastructure revenue generators: Measure A, another parcel tax that funds new parks; and Measure M, a sales tax that funds new transit. Working more closely with Metro or the county’s Regional Park and Open Space District on projects that are implemented regionally could bring stormwater capture into the design of more public spaces.

Vision 2045 also sets another very concrete target (or, more specifically, an anti-concrete target): to replace 12,000 acres of paved surfaces with new green spaces by 2045. And the most obvious candidates for greening are LA County’s schoolyards, a majority of which are paved nearly entirely in asphalt, posing a tremendous public health risk to their students in a warming climate. As the second-largest landowner in the county, managing 6,387 acres, it would make sense for LAUSD to receive a bulk of Measure W’s funds. But so far, just 10 LAUSD proposals have been submitted for SCWP grants, only one was chosen for implementation, and it was later withdrawn. That discrepancy is noted in the Vision 2045 plan, which calls for LA County schools within disadvantaged communities — currently defined by the state as the number of students who would qualify for free meals (although now all California school meals are free) — to be greened by 2030, with all schools greened by 2045. LAUSD officials are working on a major campus greening initiative but estimate that it may cost as much as $4 billion. SCWP funding could help close that gap.

But especially when a huge institution like LAUSD says it’s planning to green 30 percent of its schoolyards by 2035 on its own, the Vision 2045 goal to green 12,000 acres of impermeable surfaces by 2045 starts to seem like a literal drop in the bucket. “Why does this report ask for so much less, and farther into the future?” says Melanie Winter of The River Project. “Park needs and school greening is a fine place to begin, but are largely opportunistic low-hanging fruit and don't relate to or align with the reason we're looking to reduce hardscape. Parks and schools may give us a bit of patchwork. Methodically embedding living open spaces throughout the watershed — particularly along historic waterways — can do so much more.” Winter wants to see more nature-based solutions distributed throughout the county, from planting rain gardens to restoring urban creeks — a process known as “daylighting” — which have sprung to life in the past week in the form of flooded intersections, despite our best attempts to pave them out of existence.

The East Los Angeles Sustainable Medians Project turns the median of a residential street into a stormwater capture system that also adds shade, native plants, and walking trails. Photo by LA Waterkeeper

To that end, achieving Vision 2045’s goals will also require a systemwide overhaul in how public works departments function at the municipal level. Councilmember Katy Yaroslavsky, who worked to get Measure W approved while in former County Supervisor Sheila Kuehl’s office, introduced a motion earlier this month with several steps needed to bring LADWP’s operations and infrastructure in alignment with its many long-range climate goals, including sourcing 70 percent of its water locally by 2035. Making the city’s surfaces more spongy will also require much better interagency cooperation with the city’s Bureau of Engineering and Department of Sanitation, and even the Department of Transportation. So much of LA’s walking and biking infrastructure is built into the city’s network of grates and gutters. What does a new sidewalk or bike lane look like when the goal is to keep that water local instead of sending it down the nearest storm drain?

Angelenos have proven that we’re very water savvy. As a region we were able to dramatically curb our water use; now we use less than we did a few decades ago, despite our growing population. “We’ve made so much progress in the region in dry weather,” agrees Gold. Now, in the midst of back-to-back atmospheric river years, it’s time to bring the same attention to stormwater awareness. Even Angelenos who voted for Measure W don’t necessarily know that there are financial incentives for property owners who install stormwater interventions, in the same way local utilities offer rebates for replacing a lawn with drought-tolerant native plants. Part of that awareness means making green medians, curbside bioswales, and even simple tree plantings way more visible on every block so we can watch in real time as our cities soak up every inch. But we also need to be drawing up much more visionary plans to reconnect to our water — the types of projects that Gold says the region hasn’t executed in 50 years. “We have to have transformations like greener streets and greener schools, plus larger stormwater infiltration and capture projects,” he says. “We have to act together, more forcefully and purposely, and we’ll have more livable climate-resilient communities that benefit each and every one of us.”

Did you notice flooding in your neighborhood after the last storm? Researchers from UC Irvine and University of Miami are evaluating the benefits, costs, and tradeoffs of different approaches to manage flood risk in LA County. The first phase of the project focuses on countywide flood risk adaptation strategies — if you have thoughts about where stormwater should be captured near you, share your suggestions here.

PROGRESS REPORT

After California legalized street vending in 2018, Los Angeles adopted its own sidewalk vending program throughout the city — with the exception of eight designated no-vending zones. These included some of LA’s most-visited places: the Hollywood Walk of Fame, Dodger Stadium, and Venice Beach. In 2022, a coalition of vending advocates including Inclusive Action for the City, Community Power Collective, and East LA Community Corporation sued the city on behalf of vendors who were being excluded from these high economic opportunity areas. This spurred the council to take action, and, as of last week’s 15-0 vote, the city has finally eliminated its no-vending zones.

Vendors rallied at City Hall to demand an elimination of LA’s no-vending zones. Photo by Public Counsel

While this should be seen as a big step towards truly legalizing street vending, it still doesn’t change the fact that the city criminalized these vendors for years, in flagrant violation of state law. “The City has still not addressed the fact that enforcement of these unlawful regulations has resulted in hundreds of citations and thousands of dollars of fines issued to low income workers,” reads a joint statement from the plaintiffs. “Shockingly, even as the City acknowledges the unlawful nature of the regulations, the citations continue.” The trial begins this week.

LOCAL REPORT

Fatal overdoses have increased 1,000 percent in Skid Row since 2017, with fentanyl involved in about 70 percent of those deaths, according to a gripping In These Times report. Overdoses are also responsible for one-third of all unhoused deaths citywide, yet sweeps frequently result in the destruction of government-funded Narcan, which could prevent those overdoses.

2 LAPD helicopters are in the sky 20 hours a day, says the LA City Controller’s first-ever audit of the LAPD’s Air Support Division, which spends 61 percent of its airborne time on low-priority activities like ceremonial flyovers. This costs taxpayers about $50 million per year.

9 out of 10 LA voters think LA city ethics rules should be stronger, according to the final report of the LA Governance Reform Project, which makes recommendations to expand the ethics committee as well as giving the committee the power to place policy proposals on the ballot.

NATIONAL REPORT

JUST GIVE PEOPLE MONEY: Yet another study confirms that giving homeless people cash — in this case $750 per month in San Francisco — means they are more likely to get into stable housing.

A HISTORY OF VIOLENCE: In 2023, police killed 1,232 people in the U.S., the highest number since the Mapping Police Violence nonprofit started tracking deaths a decade ago, according to a Guardian report.

RECORDING OFF: Body-worn cameras have become a major law-enforcement investment but a major ProPublica investigation says that the technology is more often used to obscure the transparency that has been promised.

FIELD REPORT

It’s election season! Ballots for LA County voters have arrived. If you’re in LA City Council districts 2, 4, 10, or 14 and need a refresher on candidate positions, check out the videos of LA Forward Institute’s non-partisan candidate forums. If you’ve already returned your ballot — well, look at you! — you can track it here. And if you or someone you know isn’t registered to vote, you can do that online until February 20 — here’s how — then after that you can still register in person at a voting center. Ballots are due Tuesday, March 5.

REPORT IN

Hi, Alissa Walker here — I’ll be compiling Report Forward every month. Please send reports, studies, white papers, and big policy wins to me at reports@laf.institute — and forward this to someone working to make LA a better place.

Want to make sure to get these issues every month? Sign up for our email list below!